Disorders of Pigmentation

- related: Dermatology

- tags: #dermatology

Vitiligo

Vitiligo is a common acquired autoimmune condition resulting in patchy depigmentation of the skin and is characterized by the loss of function or absence of melanocytes. Its prevalence is between 0.5% and 1.0%. Affecting both sexes equally, vitiligo can occur at any age, and it can be psychologically distressing. Peak on set between 10 and 30. Clinically, it appears as completely depigmented, well-demarcated symmetric macules or patches with no scale. Its onset is insidious and asymptomatic, starting as smaller macules that gradually enlarge (Figure 19). It tends to be more visible in darker skin types (Figure 20) or in sun-exposed areas as the surrounding skin will become darker with sun exposure. The hair in the patches of vitiligo can become depigmented as well. The most commonly affected areas involve the extensor surfaces such as the dorsal hands and feet, elbows, and knees, and the periorificial areas such as around the mouth, eyes, rectum, and genitals. It can be associated with other autoimmune conditions such as diabetes and thyroid disease (check TSH or A1C).

Vitiligo is frequently associated with other autoimmune diseases (eg, autoimmune thyroid disease, type I diabetes). Studies indicate a higher incidence of autoimmune thyroid disease in vitiligo (up to 20% of patients) compared to non-vitiligo patients. The vitiligo usually precedes the onset of thyroid disease. As a result, most guidelines recommend screening vitiligo patients for **autoimmune thyroid disease and type I diabetes**. Treatment involves repigmentation with topical corticosteroids (preferred), topical calcineurin inhibitors, or ultraviolet light.

Occasionally, it can be challenging to distinguish vitiligo from other conditions that cause depigmentation such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, tinea versicolor, pityriasis alba, and leprosy.

Postinflammatory hypopigmentation

Postinflammatory hypopigmentation is a loss of skin pigmentation following resolution of inflammatory or infectious dermatoses. Topical or intralesional glucocorticoids can also cause hypopigmentation, which can be difficult to distinguish from postinflammatory hypopigmentation. Upon cessation of the glucocorticoid, the pigmentation will typically return. Other causes of postinflammatory hypopigmentation may include chemical irritants and destructive therapeutic procedures such as cryosurgery or laser therapy. The diagnosis of postinflammatory hypopigmentation is based upon recognition of hypomelanotic or amelanotic macules or patches that correspond to previous inflammatory lesions. If the diagnosis is in doubt, a skin biopsy may assist in identifying the responsible inflammatory lesion. Postinflammatory hypopigmentation typically resolves without specific therapy over weeks to months.

Tinea Versicolor

The diagnosis of tinea versicolor can be verified with a potassium hydroxide preparation showing hyphae and yeast cells. In addition, Wood lamp examination may disclose yellow to yellow-green fluorescence.

Pityriasis alba occurs in children and adolescents. Defining characteristics include patches of hypopigmentation on face, neck, upper trunk, and proximal extremities. Lesions typically manifest some border irregularity and are associated with a fine scale.

Tuberculoid leprosy presents with a small number of hypopigmented anesthetic lesions with raised margins.

Partial or complete depigmentation is also seen in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, a very common hypopigmentation disorder. Guttate hypomelanosis manifests as 2- to 6-mm hypopigmented round or oval macules on the trunk and extremities of middle-aged and older persons (Figure 21). Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis may be the results of chronic ultraviolet (UV) exposure, trauma, and normal aging.

Other causes of depigmentation include drug-induced leukoderma and melanoma-associated leukoderma. Leukoderma has been reported in patients with advanced melanoma treated with immunotherapy such as high-dose interleukin-2, interferon alfa, ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Some genodermatoses such as tuberous sclerosis, piebaldism, and Waardenburg syndrome also cause depigmentation.

History and physical examination including a Wood lamp examination to help accentuate the depigmentation and the distribution of the lesions will help confirm the diagnosis. Lesions due to complete absence of melanin, such as vitiligo, will appear bright white and sharply delineated when examined with a Wood light. This is most helpful to identify hypopigmented or depigmented lesions in fair-skinned persons that otherwise may not be visible. Vitiligo can be associated with other autoimmune conditions such as diabetes mellitus and thyroid disease. Those conditions should be screened for, but otherwise treatment involves methods to normalize the pigmentary discrepancies.

Treatment for depigmented skin can be challenging, prolonged, and suboptimal. Topical therapies involve high-potency topical glucocorticoids or immunomodulators (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus). Phototherapy with UV light is also an option and can be the treatment of choice for widespread involvement. Repigmentation occurs first around hair follicles as they are thought to be the reservoirs for melanocytes. As a result, repigmented skin will initially have a speckled appearance. Depigmentation therapy can also be considered if the vitiligo is so widespread that there are only a few remaining islands of normal pigmented skin. Monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone can be applied to the remaining normal islands of skin to permanently destroy the melanocytes.

Melasma

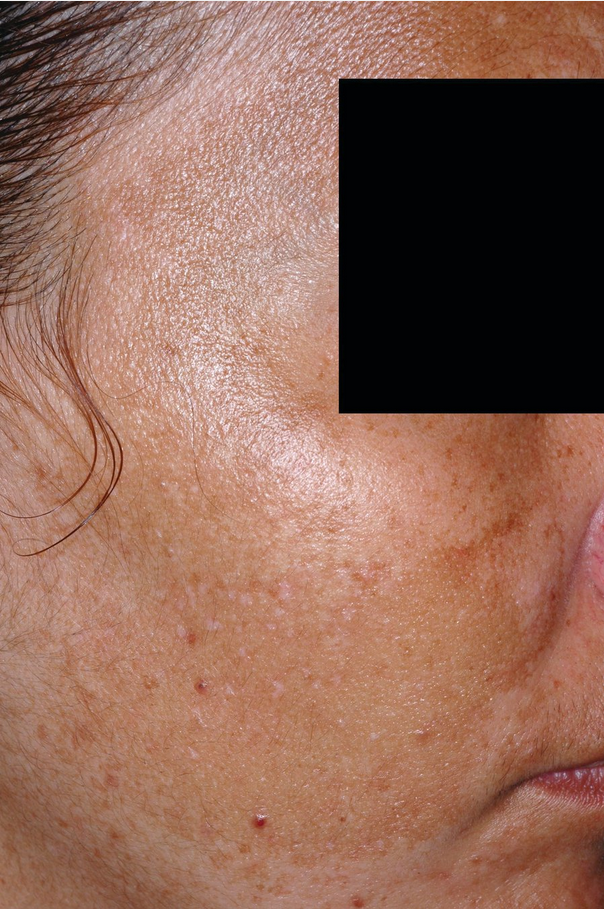

Melasma, also known as chloasma or the mask of pregnancy, is a common acquired condition resulting in patchy hyperpigmentation of the skin on the face. It can also be seen on the upper extremities. In this condition, the melanocytes overproduce melanin due to a multitude of factors including ultraviolet radiation, genetic predisposition, and hormonal influence (pregnancy, oral contraceptives). Women and those with darker skin types are more commonly predisposed. Clinically, it presents as ill-defined, tan to dark brown, reticulated patches mostly on the sun-exposed areas of the face (malar, mandibular, and centrofacial regions) (Figure 22). Pigmentation can develop rapidly, often over weeks. It worsens with sun exposure. The main differential diagnoses include postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, freckles, and lentigines. Melasma will fade during the postpartum period with sun protection and discontinuation of oral contraceptives. It will take months to years for pigmentation to normalize.

Ill-defined, reticulated hyperpigmented patches on malar cheeks typical for melasma.

Ill-defined, reticulated hyperpigmented patches on malar cheeks typical for melasma.

Treatment can be challenging and prolonged. The mainstay of treatment is strict sun protection, avoidance or discontinuation of the causative factors, and bleaching agents. Hydroquinone is typically used with concentrations ranging from 2% (over the counter) to 4% (prescription). The use of hydroquinone should be monitored as it can cause drug-induced ochronosis, a bluish-gray discoloration. There are combinations of hydroquinone, tretinoin, and glucocorticoid topical creams that can be used nightly. Chemical peels can also help improve appearance. Laser and light-based therapies are another option for patients with refractory melasma, although they are used with caution as they can flare melasma as well. Caution must be used for darker skin types as irritating topical agents can result in inflammation and worsen pigmentation with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Post inflammatory pigmentation

Postinflammatory hyper- or hypopigmentation can occur after any cause of natural or iatrogenic-related inflammation (acne, dermatitis, folliculitis). Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is most common in those with skin of color. It presents as hyperpigmented macules or patches at sites of previous inflammation. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation can cause significant psychological stress and can take months to years to resolve. The first step in treatment is to treat the underlying skin condition causing the inflammation. Hydroquinone can be used and when used in combination with tretinoin, it can augment its effect. Lasers and chemical peels can also be used with caution as any therapy that is irritating can be counterproductive.